Many children struggle with reading because they haven’t developed strong phonological awareness skills that help them recognize sound patterns in words.

Teachers often notice students who struggle to hear rhymes or have difficulty connecting words that sound similar.

This blog will demonstrate that rhyming builds phonemic awareness, supports memory development, and creates neural pathways for reading success.

You’ll find engaging activities, games, and teaching techniques that work across different age groups.

The Basics of Rhyming

Rhyming happens when words share the same ending sound. Words like “cat,” “bat,” and “hat” rhyme because they all end with the “-at” sound. This creates a musical quality that children naturally enjoy.

Children typically develop rhyming skills between the ages of 3 and 5 years old. They start by recognizing rhymes in familiar songs and nursery rhymes. Later, they learn to create their own rhyming words.

Rhyming is when some words build phonemic awareness skills. Children who can hear rhymes develop stronger abilities to break words into individual sounds. This skill directly supports reading and spelling success.

The brain creates neural pathways when children practice rhyming regularly. These connections help with pattern recognition and language processing.

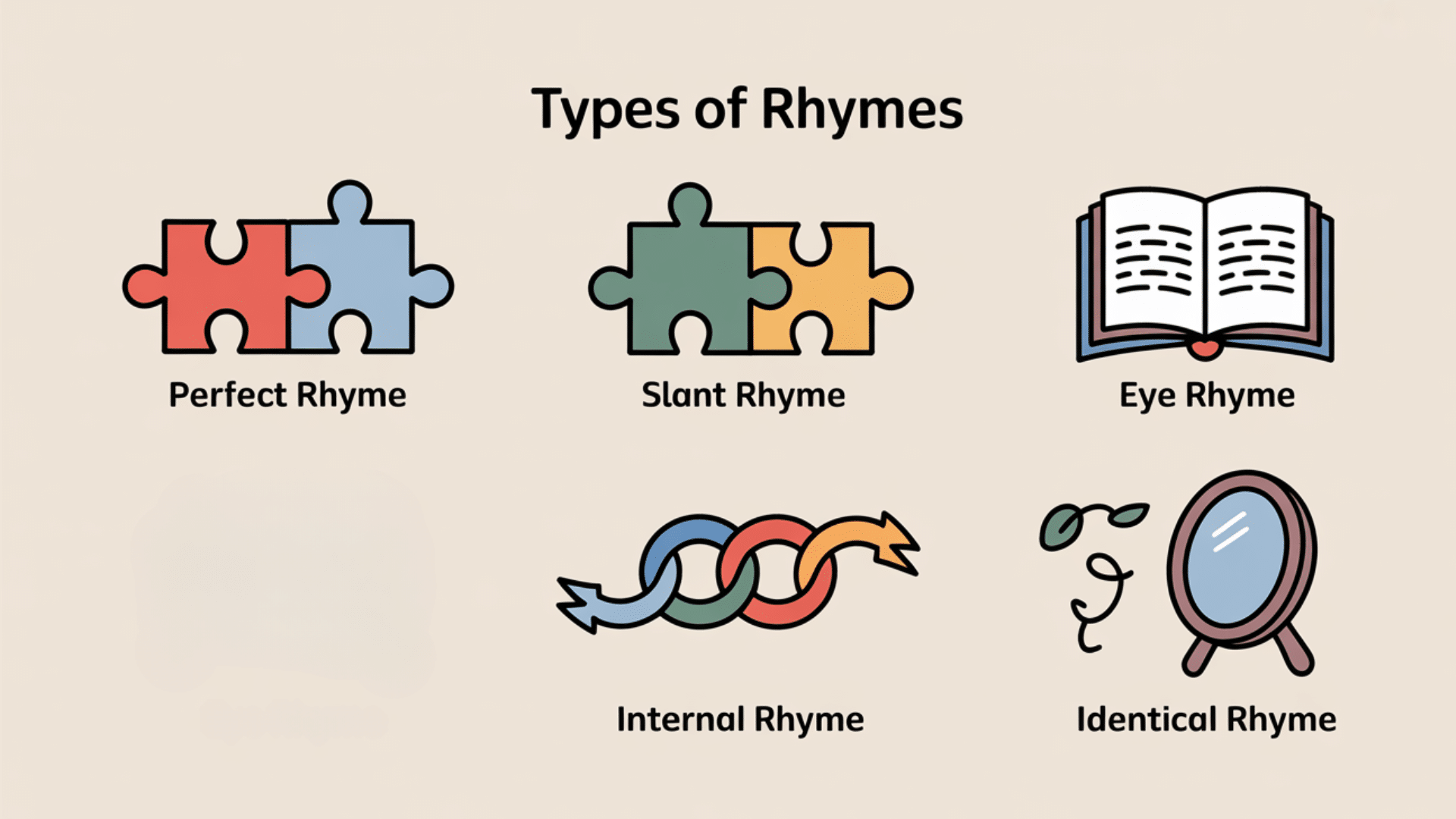

Types of Rhymes

Different types of rhymes create various sound patterns and learning opportunities for children.

Understanding these categories helps teachers and parents select suitable activities that cater to multiple skill levels and educational objectives.

1. Perfect Rhymes (True Rhymes)

Perfect rhymes share identical sounds from the vowel to the end of the word. These create the strongest sound connections and are easiest for children to recognize and produce.

Examples include “cat/hat,” “make/cake,” and “light/night.”

Children typically master perfect rhymes first because the sound patterns are most apparent. These rhymes appear frequently in nursery rhymes, songs, and early reading books. They provide clear examples for teaching rhyming concepts.

2. Near Rhymes (Slant Rhymes)

Near rhymes have similar but not identical ending sounds. Examples include “orange/door-hinge” and “love/move.” These rhymes are more challenging for young children to recognize, but they expand vocabulary and creativity.

Advanced learners enjoy exploring near rhymes in poetry and songwriting. They require more refined listening skills and an understanding of sound variations.

3. Eye Rhymes (Visual Rhymes)

Eye rhymes look like they should rhyme based on spelling, but sound different when spoken. Examples include “love/move” and “cough/rough.” These demonstrate how English spelling doesn’t always match pronunciation.

Children encounter eye rhymes in reading activities. They learn that visual patterns don’t always predict sound patterns. This understanding helps with spelling and reading comprehension skills.

4. Multisyllabic Rhymes

Multisyllabic rhymes involve words with multiple syllables that share ending sounds. Examples include “running/stunning” and “beautiful/dutiful.” These rhymes challenge children to hear patterns in longer words.

Advanced preschoolers and school-age children enjoy multisyllabic rhyming games. These activities build phonological awareness in complex words. They prepare children for reading longer, more complex vocabulary words.

5. Internal Rhymes

Internal rhymes occur within single lines of poetry or songs rather than at line endings. Examples include “I went to town to buy a gown,” where “town” and “gown” rhyme within the same line.

These rhymes add musical quality to language and help children recognize sound patterns in different positions.

They appear in many children’s songs and poems, creating memorable language experiences.

Rhyme Schemes in Poetry

Rhyme schemes are the patterns poets use to organize rhyming words in their poems. These patterns create rhythm and music that make poems memorable and enjoyable to read aloud.

AABB – Couplet Pattern

Lines rhyme in pairs, creating a bouncy, sing-song quality. This pattern makes poems easy to memorize and gives quick satisfaction with each rhyming pair.

“Twinkle, twinkle, little star, (A)

How I wonder what you are. (A)

Up above the world so high, (B)

Like a diamond in the sky.” (B)

ABAB – Alternating Pattern

The first and third lines rhyme, and the second and fourth lines rhyme together. This creates a flowing, conversational feel with delayed rhyme resolution, building anticipation.

“Mary, Mary, quite contrary, (A)

How does your garden grow? (B)

With silver bells and cockleshells, (A)

And pretty maids all in a row.” (B)

ABCB – Simple Ballad Pattern

Only the second and fourth lines rhyme, perfect for storytelling. This pattern creates a natural, speech-like quality ideal for narrative poems.

“Jack and Jill went up the hill (A)

To fetch a pail of water. (B)

Jack fell down and broke his crown, (C)

And Jill came tumbling after.” (B)

Rhyming Beyond Poetry

Rhyme doesn’t just live in poetry books – it’s everywhere around us, making language more memorable, catchy, and fun.

| Category | How Rhyme is Used | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Music & Lyrics | Creates catchy, memorable hooks and emotional depth in songs. | Pop songs, rap verses, Eminem’s multi-syllabic rhymes |

| Advertising | Makes slogans sticky and simplifies complex brand messages. | “The snack that smiles back – Goldfish”, “Don’t be vague, ask for Haig” |

| Everyday Language | Adds rhythm, memory aid, and fun to conversations, advice, and childhood chants. | “No pain, no gain”, “Fake it till you make it”, “See you later, alligator.” |

The Cognitive Impact of Rhyming

Rhyme does more than create pretty sounds – it changes how our brains process and remember information.

Memory and Learning

Rhyming acts like mental Velcro, helping information stick in our minds much longer than plain text.

Young children, in particular, benefit because their developing brains naturally seek out sound patterns and repetition.

Neuroscience research indicates that rhyming activates multiple brain regions simultaneously, including those involved in language processing, memory formation, and pattern recognition. This creates stronger neural pathways than non-rhyming information.

Persuasion and Perception

The “rhyme-as-reason” effect reveals that rhyming statements seem more truthful than identical non-rhyming versions. Our brains interpret the fluency of rhyming language as an indicator of accuracy.

“What sobriety conceals, alcohol reveals” sounds more insightful than “What sobriety hides, alcohol shows.” “An apple a day keeps the doctor away” feels more authoritative than “Daily apple consumption promotes health.”

Tips and Techniques for Crafting Rhymes

Creating effective rhymes requires practice and understanding of sound patterns, rhythm, and word relationships.

These practical techniques help writers develop stronger rhyming skills while avoiding common pitfalls that make rhymes sound forced or awkward.

- Start with perfect rhymes – Use words with identical ending sounds like “cat/hat” before attempting near rhymes.

- Read your rhymes aloud – Hearing the rhythm reveals awkward patterns that look fine on paper.

- Avoid forced rhymes – Don’t twist sentence structure unnaturally to make words rhyme.

- Use slant rhymes strategically – near rhymes, such as “love/enough,” add sophistication when perfect rhymes feel too obvious.

- Consider syllable patterns – Match syllable counts between rhyming lines for better flow.

- Focus on meaning first – Strong content matters more than perfect rhymes.

- Experiment with internal rhymes – Rhymes within lines add musical quality without following strict patterns.

The Bottom Line

Rhyme weaves through our lives in countless ways, from childhood songs to advertising jingles to everyday expressions.

This magical quality of language connects words, ideas, and memories in ways that plain speech cannot match.

The techniques and insights explored here reveal the true power of rhyme beyond simple wordplay. Understanding how rhyme affects memory, persuasion, and learning helps us appreciate its role in communication.

Accept rhyme as a tool for creativity, connection, and communication. The magic of rhyming words continues to shape how we think, learn, and express ourselves.